Andrew Mendez

Welcome!

My name is Andrew and I am currently transitioning into the world of data from 10+ years in the restaurant industry. Here are the projects I've been working on!

View My LinkedIn Profile

Flotation Plant Exploration

A Python Playground

This is the 4th Project that I posted working through the Data Analytics Accelerator Bootcamp led by Avery Smith. I was introduced to Python and its incredible power!

This project is a little different compared to the first three I wrote from this bootcamp. My intention for this project was for it to be a more “skill share” format where I’m describing what I’ve learned and when, or how, to use specific functions when manipulating and diving into the data. I used a real dataset that came from a Flotation Plant from March to September 2017. (You can access the dataset here)

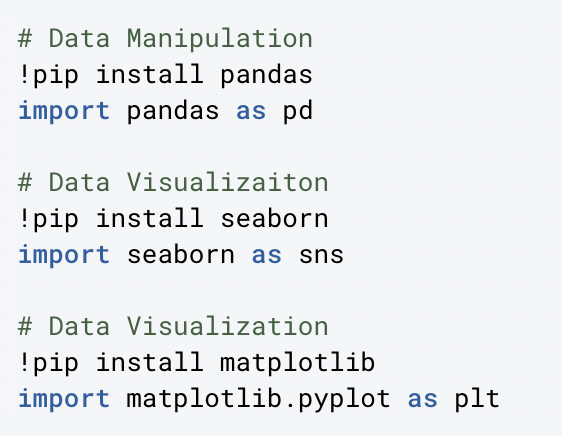

Installing IDE’s

I was very interested to learn about IDE’s (Integrated Development Environments). These libraries are one of the key reasons by Python is such an incredibly powerful platform for data analysis.

My first step in this Python Playground was to install these IDE’s using !pip install. I used Pandas (data manipulation), Seaborn (data viz) & Matplotlib (data viz).

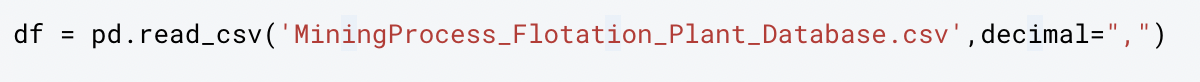

Uploading Database Into Deepnote

Next, I uploaded the Flotation Plant data into Deepnote, and then introduced it into my Deepnote notebook.

In this code, I am naming a variable “df” (dataframe) to be the CSV file I uploaded containing the data. I’m telling Python that I’m using the Pandas function to read the CSV file: pd.read_csv() and then including the decimal command to replace the commas in the file with decimals to ease of reading.

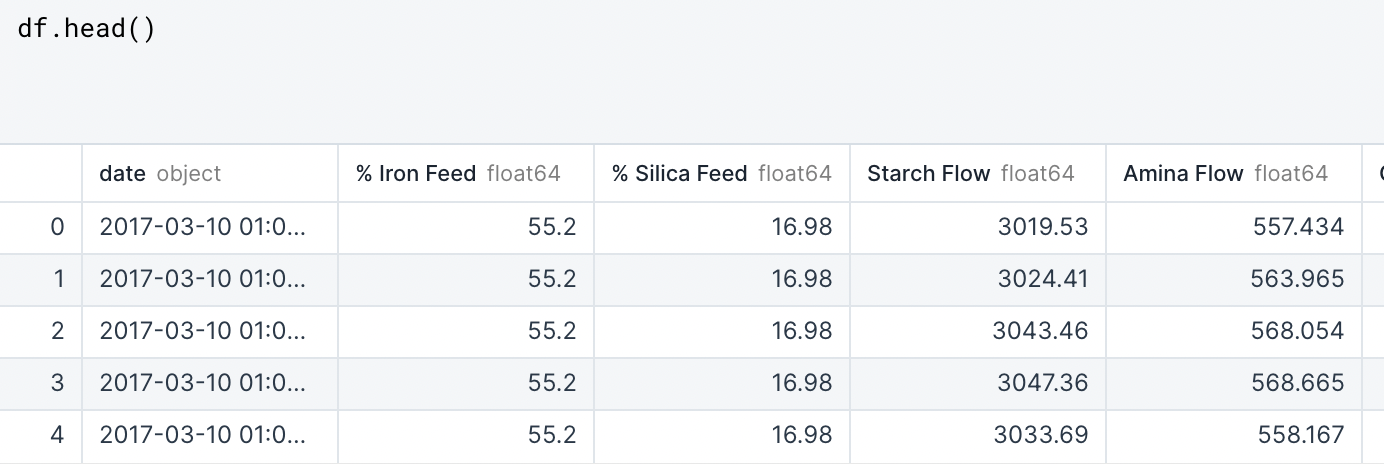

Getting to Know This Dataframe

One of the important first steps that Data Analysts should NEVER skip is to get to know the data that you are working with! In other words, what does each series represent (the columns in Pandas), what’s the shape of the dataframe you’re working with, are there any NULL variables present, how are the series formatted, is there any missing or incomplete data, what is the range of the data, etc.

First, I used the head function to get a preview of the first 5 rows of data in the dataframe (first five rows is the default when no parameter is set within the parenthesis in this function).

I also want to point out here that Python is based on a “Zero Index” where zero represents the FIRST value, which is why in the above graphic we see that the first row has an index of “0”. This is also important to remember when using .iloc, for example, which we’ll visit later on.

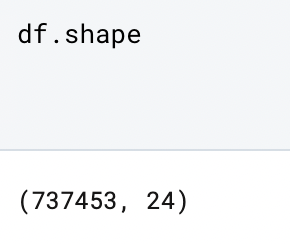

Shape of the Dataframe

Next I wanted to know the overall shape of the data I was working with, so I used the shape function:

Here Python returns these two values encased in paranthesis and separated by a comma. The first value in this set is the total number of rows (737,453) and the second number is the total number of series (24) in the dataframe. This format, (rows, series), is important to understand as well as it applies to other functions as well.

List of Series

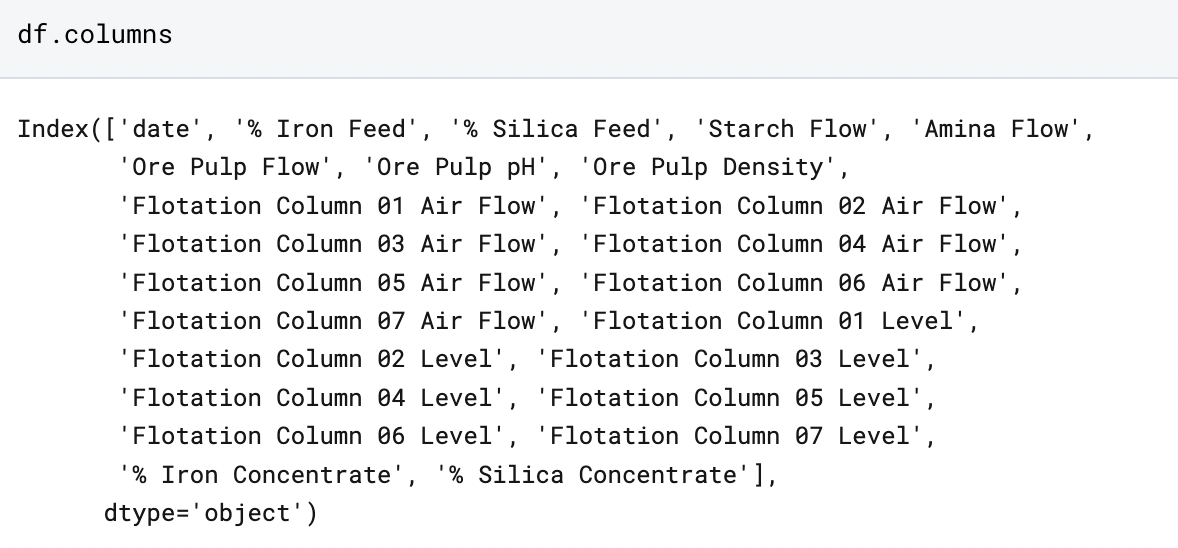

Let’s take a look at a list of all the series in our dataframe:

Python returns a list of all the series present. The list here is represented by the data encased within square brackets INSIDE of the parentheses, and all the data separated by commas and single quotations.

Next, let’s take a look at a single series. Python gives us an overview of the series specified, in this case the “date” column:

It returns the first five and last five rows, and gives us the Name, Length, and datatype. Note, here, that the length that Python returned was 737, 453, which matches the total number of rows returned when we used the shape function. But on the left column, the last row comes up as 737, 452! This is the result of the “Zero Index” functionality: the first row here is indexed as “0”, therefore the length is accurate even though the index is not the same.

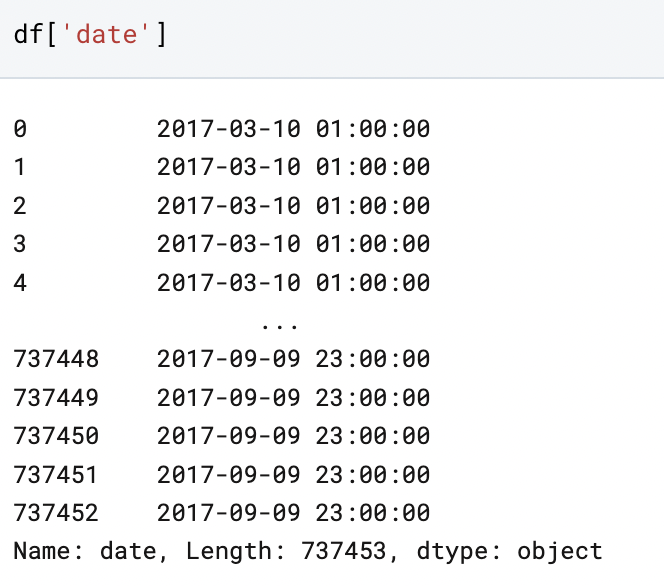

Using describe()

This function returns a count, mean, standard deviation, min, max, and the quartile values of each series. This is an extremely useful function that can further help you get a more bird’s-eye-view of your data.

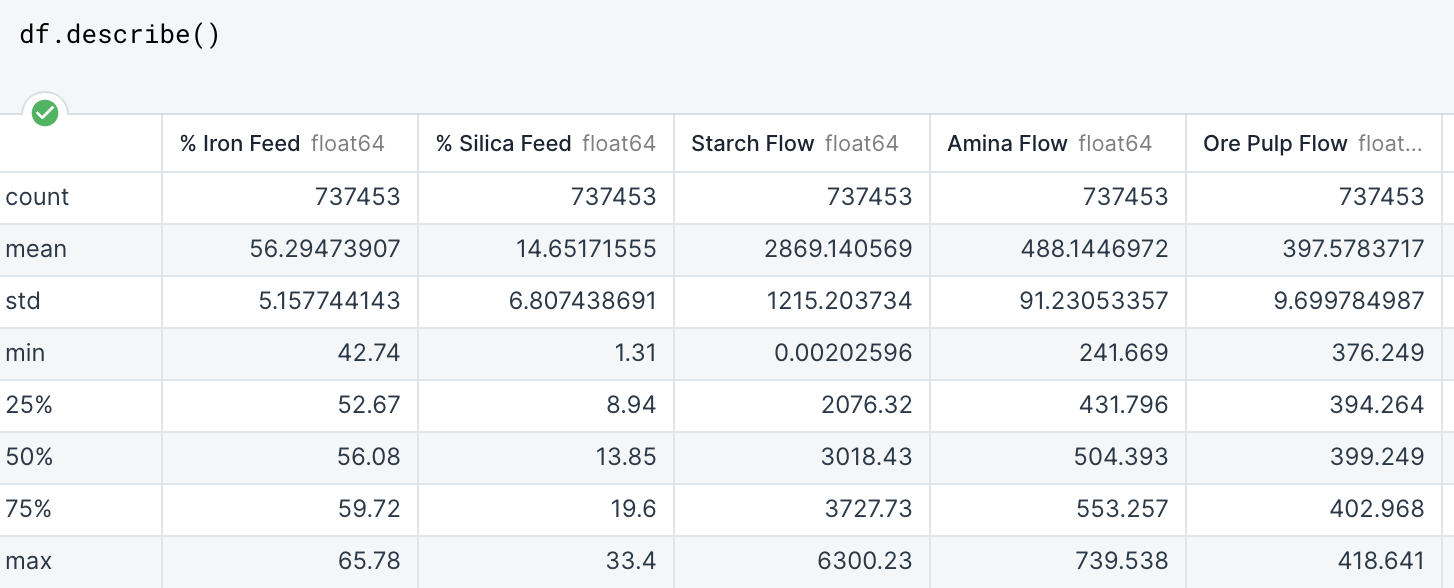

The Timeframe

Another important parameter to be considered is the dates in which the data occurred. We’ll use a simple “min” and “max” function to determine the timeframe we’re exploring with this data:

In this code, I’m naming a variable for each value and naming it as the “min” and “max” value of the series “date_clean” and asking Python to print it using text and the variable in a string. Thus, returning the “min” and “max” dates in two sentences.

Data Manipulation

When we are looking at data in Python, we will need to be able to select SPECIFIC data in order to answer business related questions and to add value to the business.

An important function to know to do this in Python is the Index Location function:

Here, I am telling Python that I want it to return rows 1-2 which is represented as 0:2 on the left side of the comma. The colon here represents “in between”, Python will return the first and second row, but not the third (index 2). The same applies for the series 0:2 which returns the first two columns.

If you wanted to specify the first two rows, but ALL of the columns in the dataframe, you would add a colon “:” to the right side of the comma.

Further specifying specific rows and series would be encased within square brackets signaling to Python that there is a list.

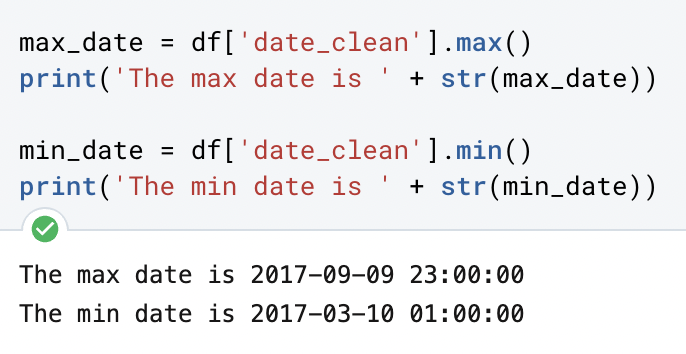

Discovering the Data Types

Data types are important when manipulating data because you want to make sure that the platform you’re using is treating the data appropriately so that your insights are accurate and for your visualizations to populate smoothly.

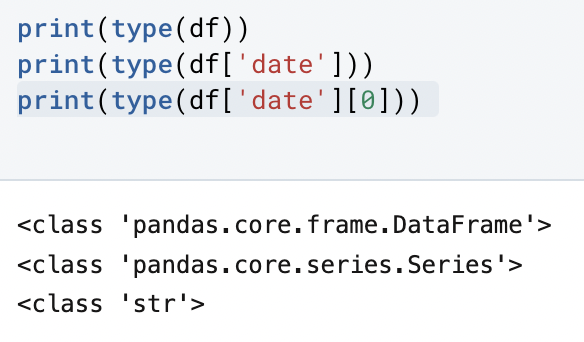

I used the type() function:

Here, we’re asking Python to print three things: the first is the datatype of “df” which is our dataframe, the second is asking about the series titled “date”, and the third is asking about the first value present in the series “date”.

The first two rows that Python returned match what we expect them to, but the third shows that the values in the “date” series are formatted as a string and not as an actual date.

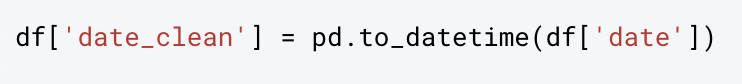

To fix this, we use the .to_datetime function in Pandas:

Here we’re also naming a new series (or column) in the “df” dataframe to BE the series “date” but formatted as a datetime.

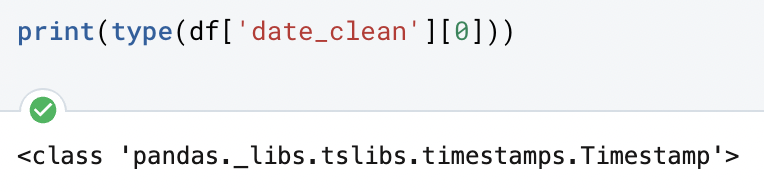

To check this, we used the same function as above:

This shows the first value in the “date_clean” series is formatted as a timestamp in Pandas.

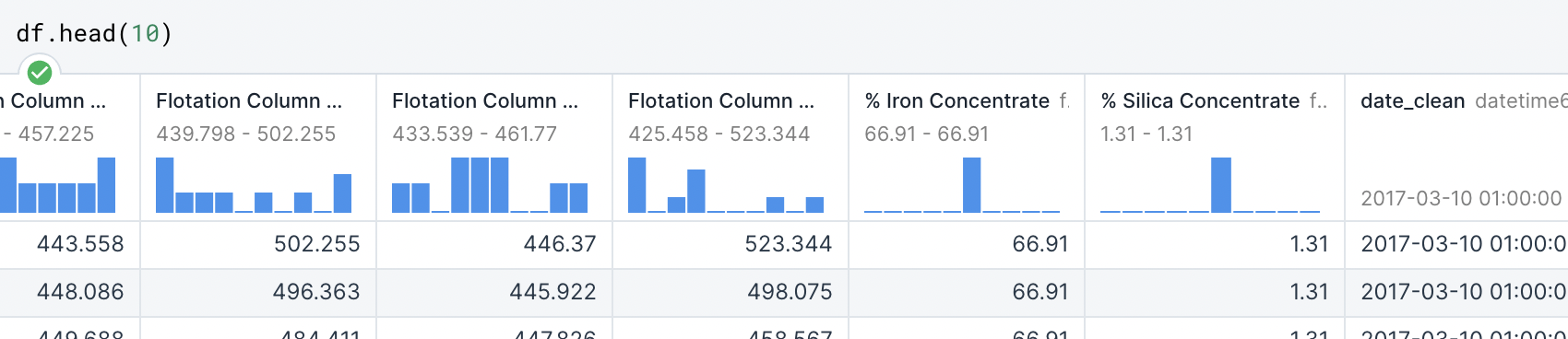

To double check that the series was created in the dataframe, we can use head once more:

Let’s Specify!

Let’s say that I am asked to look at specific columns in regards to specific data!

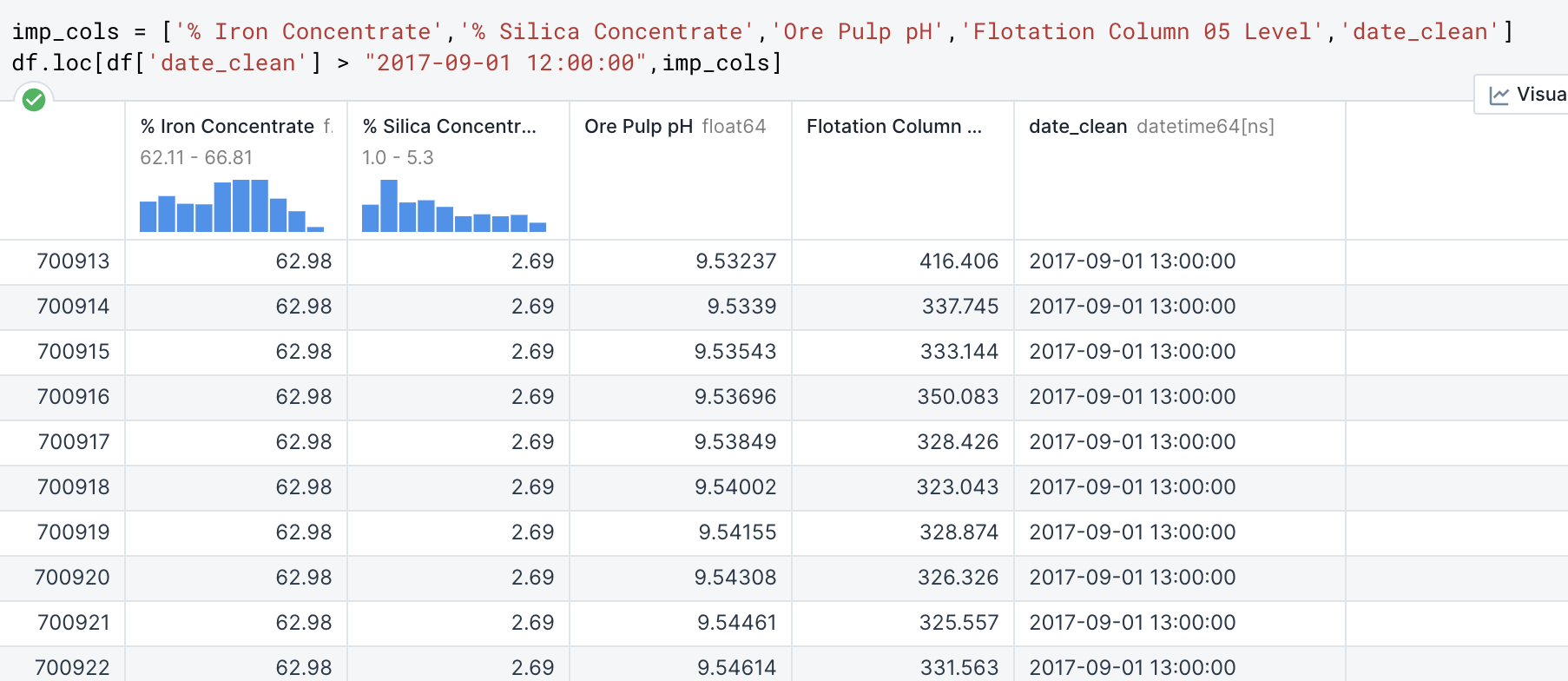

Let’s say the Flotation Plant is looking at: % Iron Concentrate, % Silica Concentrate, Ore Pulp pH, Flotation Column 05 Level and all the data AFTER September 1st after 12pm. I will name a variable to equal the list of columns that we’re looking at and include the date for further clarity.

I then use .loc and specify that the rows I want returned need to be greater than Sep 1st at 12pm using the “date_clean” series and with those rows I want to look at “imp_cols” which include all the information that the plant is most interested in.

This method is very useful in trimming down the database to pinpoint data that is relevant to the questions that are being asked. The use of variables in this instance helps to streamline my code so that I can efficiently manipulate the data to find the answers I’m searching for.

A Change in Parameters

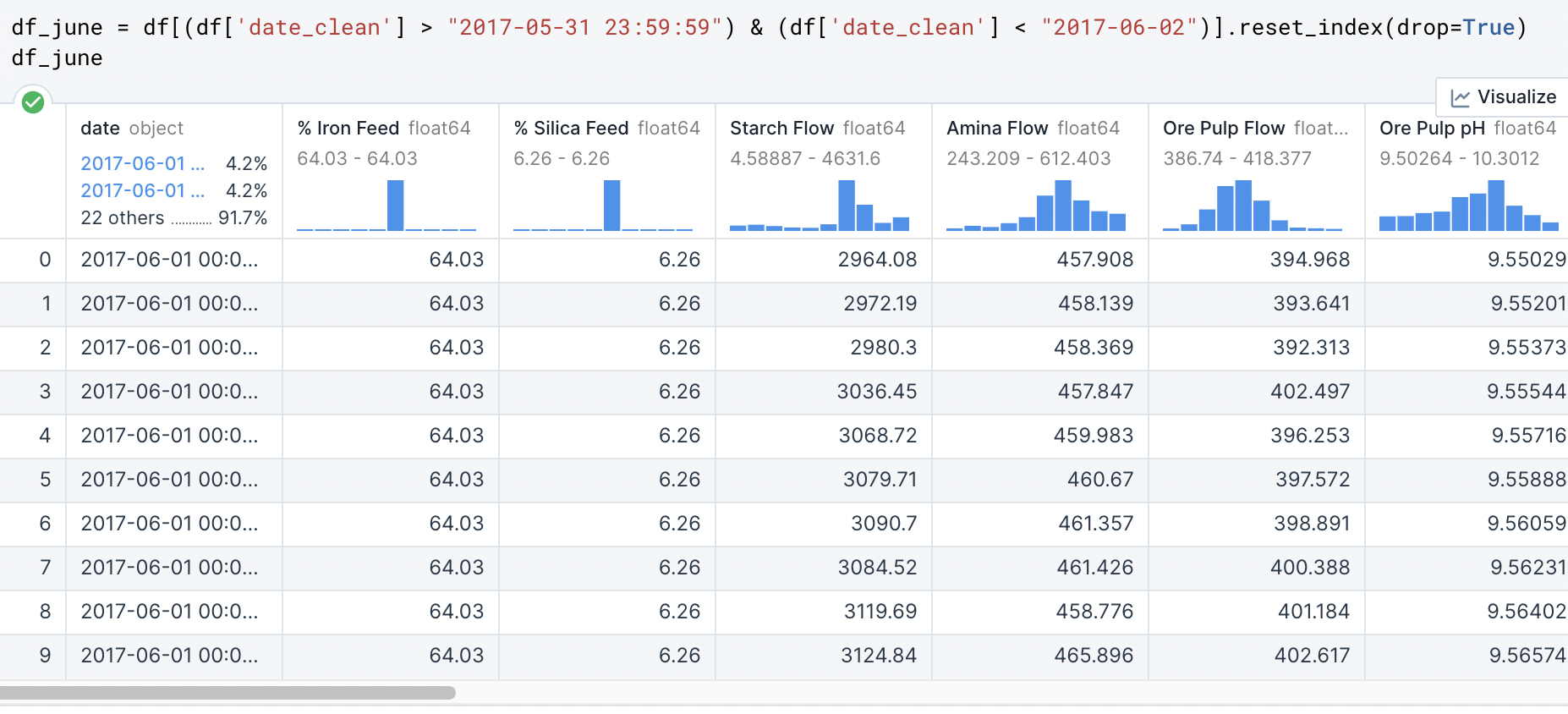

Now, my contact at the Flotation Plant is asking if I could extract data specifically between the dates of March 31st and June 2nd. Since this data is significant in my research to find insights, I am going to create its own dataframe and reset the index.

I am asking Python to search within “df” the dates that are greater than March 31, 2017 @ 11:59pm AND less than June 2, 2017 within the “date_clean” series and then after returning those rows to RESET the index to finalize the NEW dataframe that I am naming “df_june”.

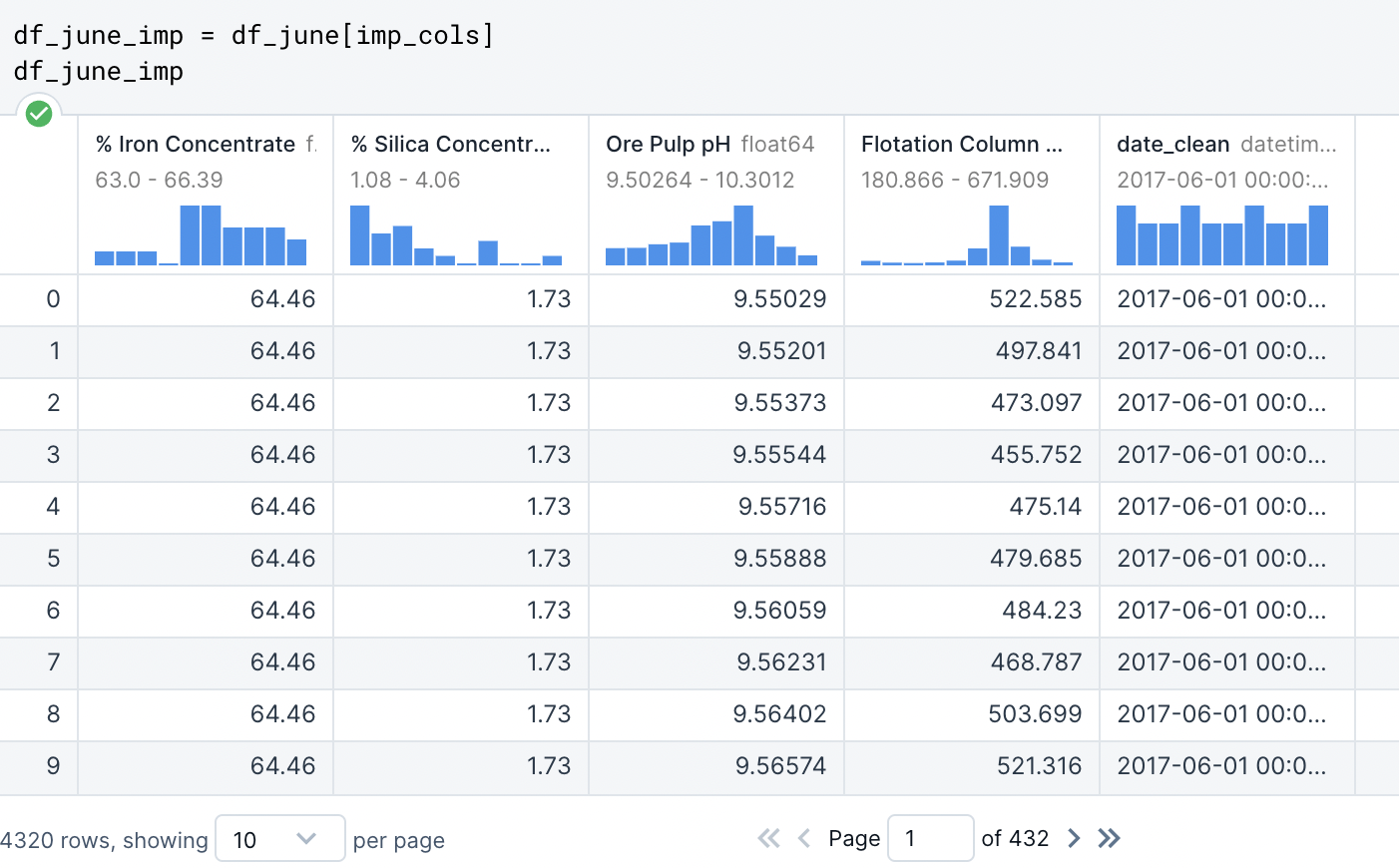

We want to use rows in this newly created dataframe, “df_june”, to include ONLY the important columns that we labeled earlier.

We are now naming another variable to be defined as the “df_june” dataframe displaying its rows using only the data included in “imp_cols”.

This helps to further dial into the data that will help provide some answers to the questions that the Flotation Plant is posing.

Data Visualization in Python

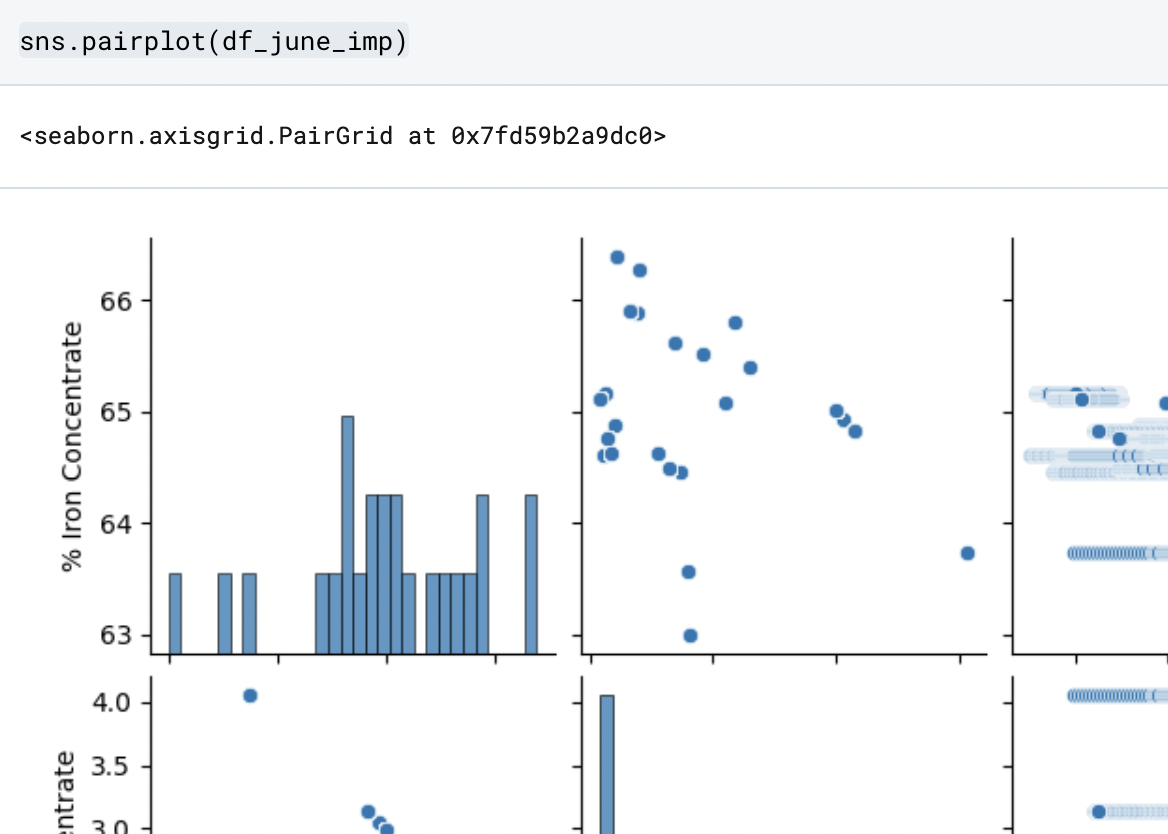

To be able to visually evaluate, and later present, this data, we will be using Seaborn next to execute a Pairplot:

In this code, I’m utilizing the IDE Seaborn, represented as sns, and executing the function .pairplot on the dataframe “df_june_imp”. This displays a 4x4 grid which compares two variables in multiple instances simultaneously. This allows for quick analysis of the variables in the dataframe and allows the possibility of noting any relationships quickly. (You can access the entire Pairplot here)

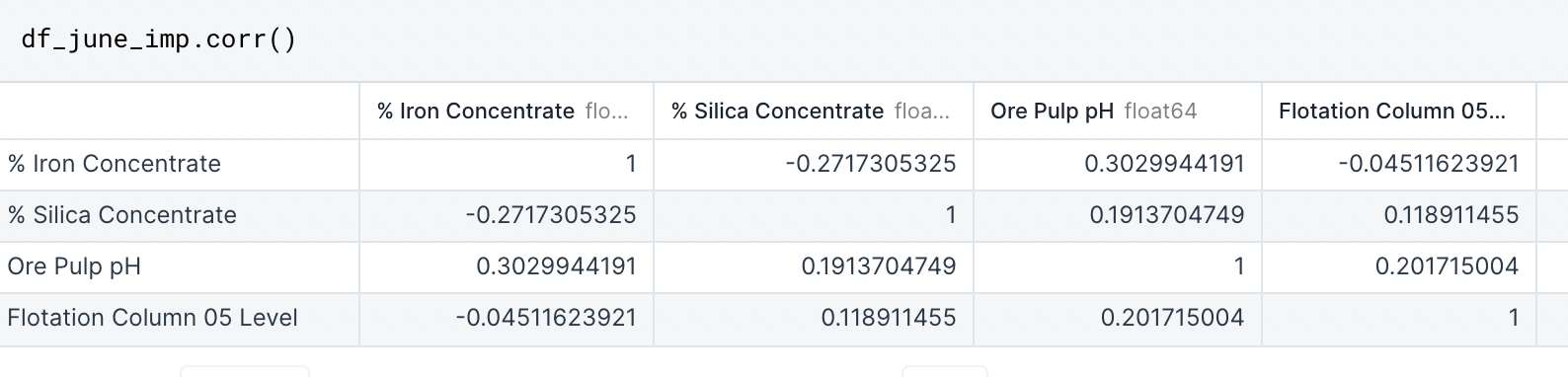

Is there any significant correlation?

In the case that you wanted a numerical correlation to further validate your hypothesis after looking at the pairplot, you can ask Python to run the correlation function:

This function that provide further evidence for your findings once you present this your key insights from the data.

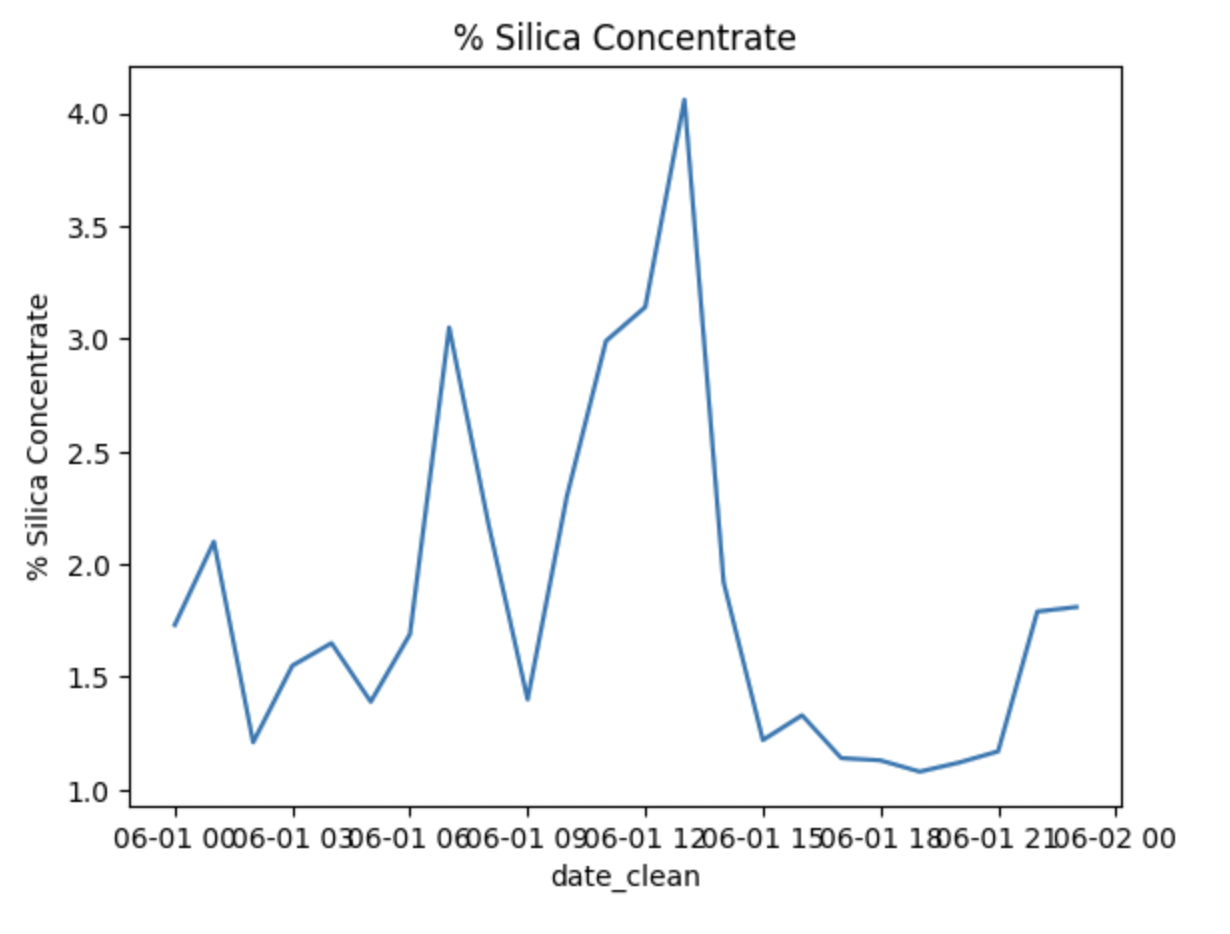

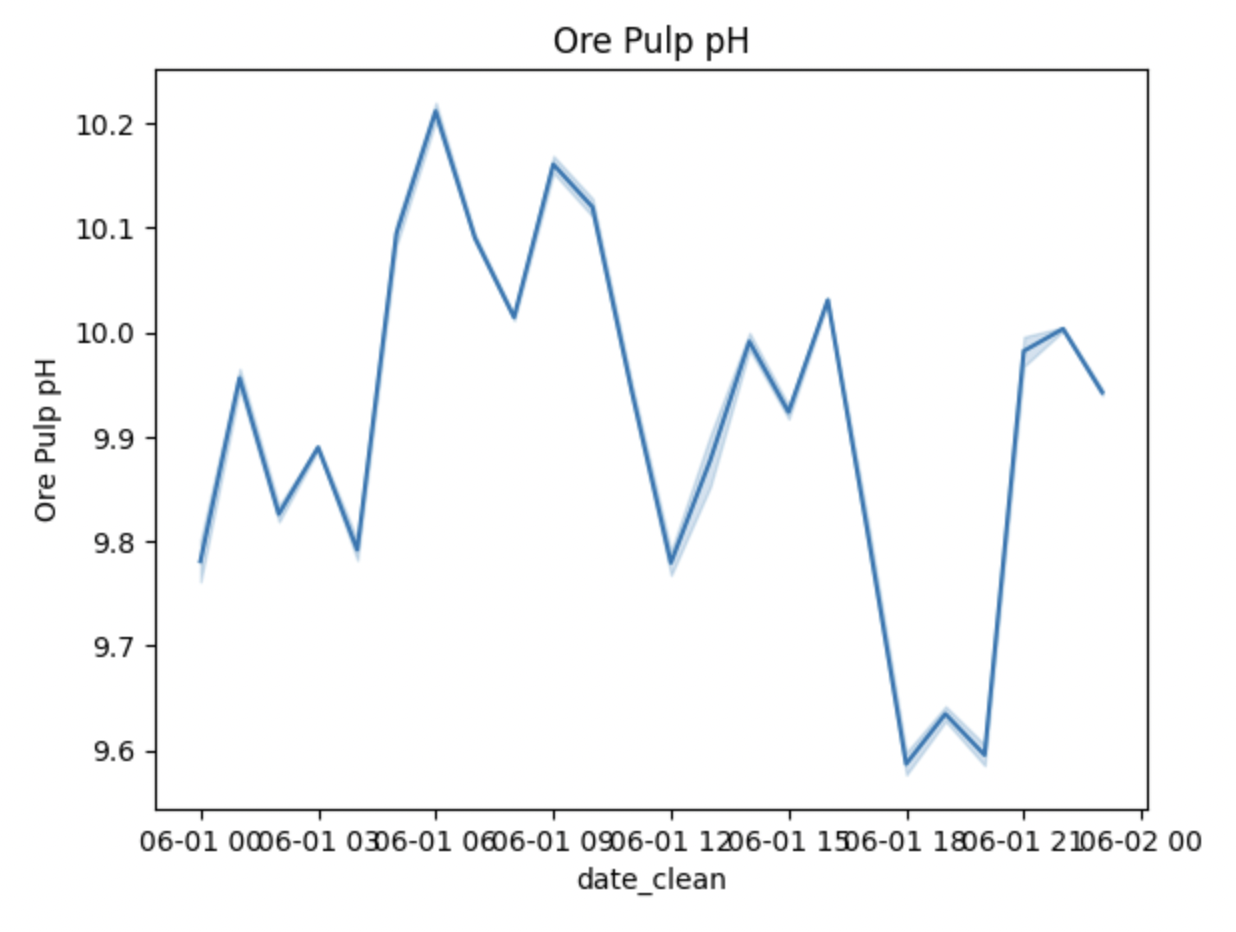

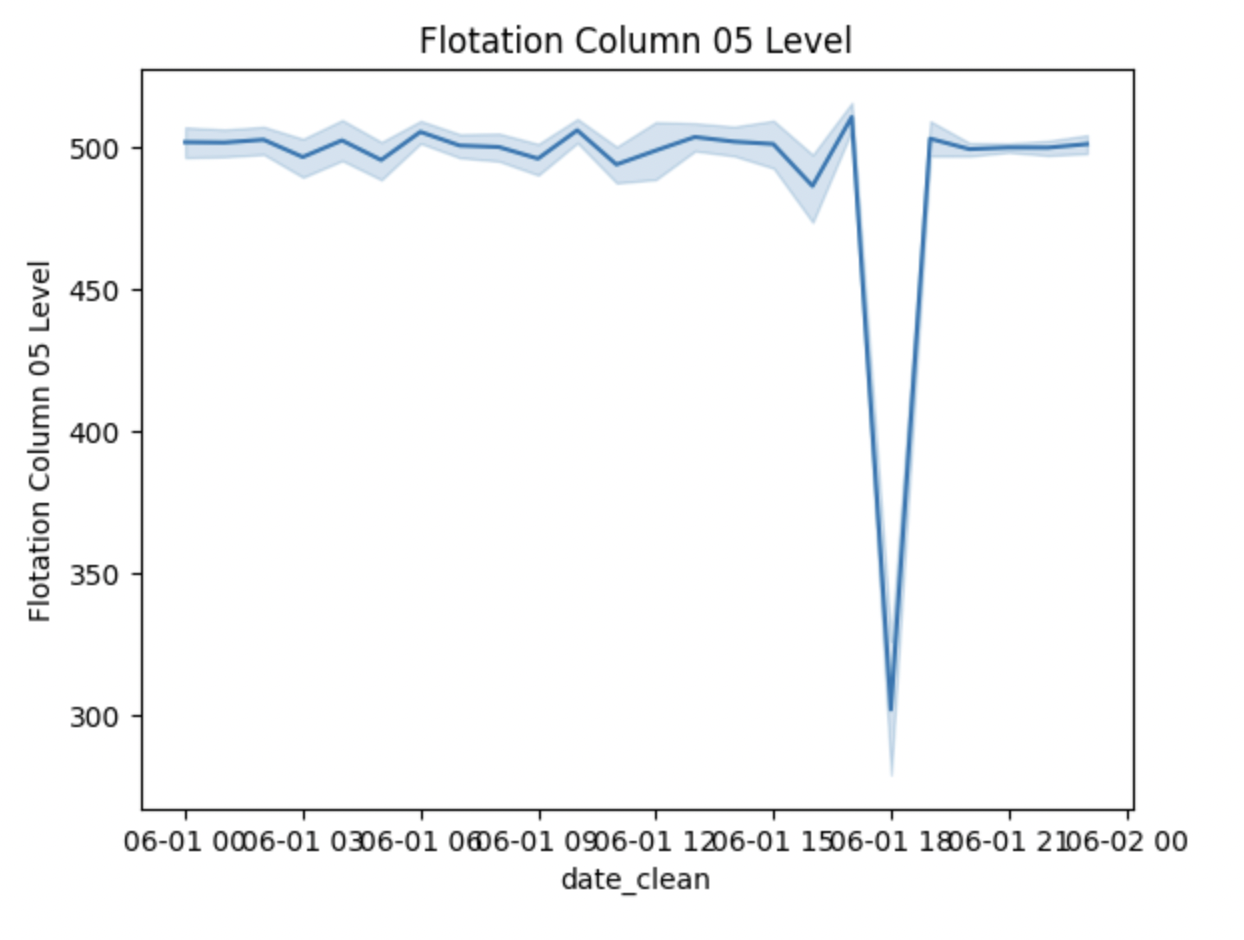

Lineplots

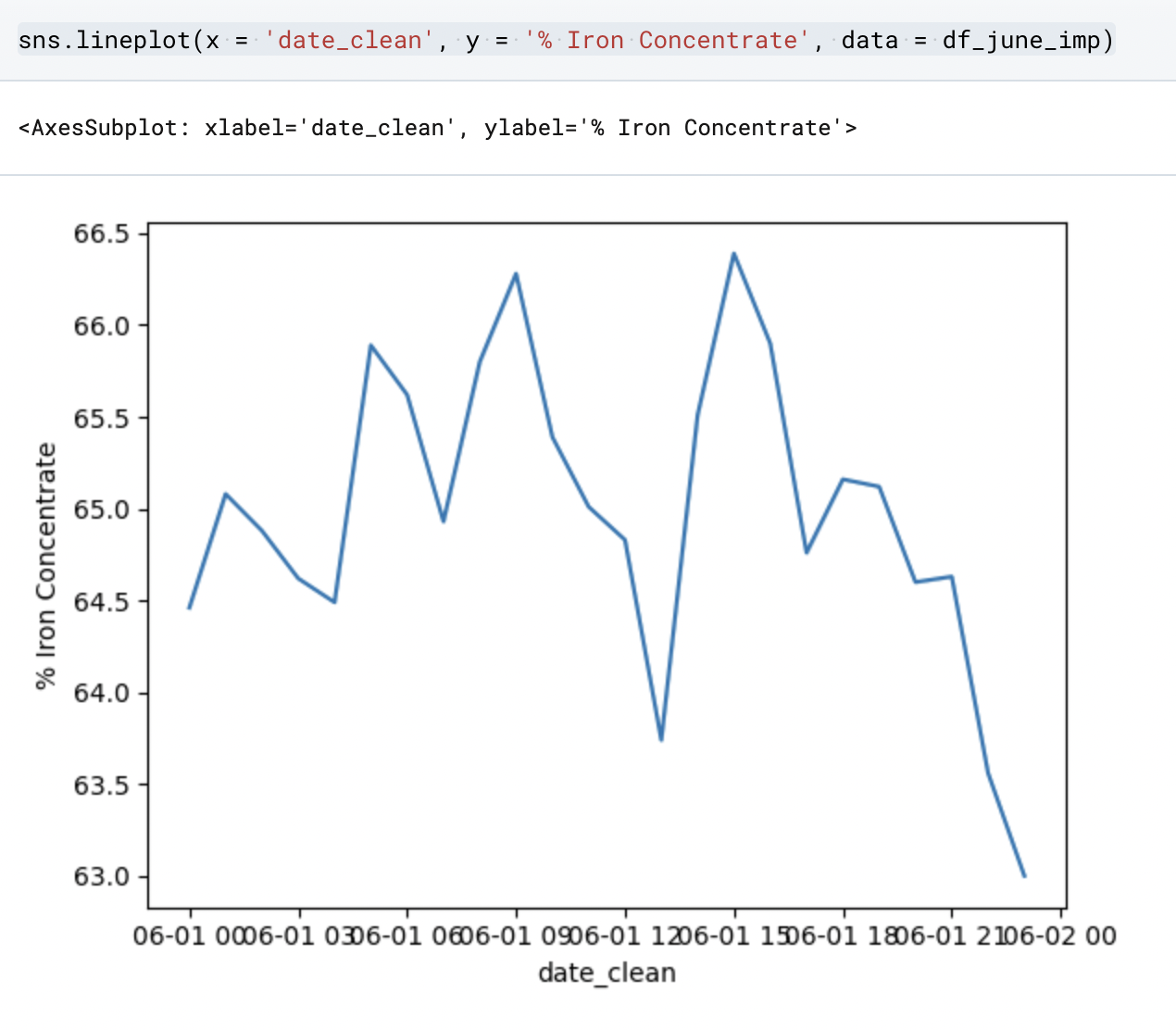

If you wanted to present the information in a more widely used lineplot, we could use Seaborn again to create one:

Here we are asking Python to use the lineplot function from Seaborn (sns) and we’re outlining the parameters for x & y and where the data is located.

We could write this code multiple times to create a lineplot for each of the other series of interest, or we could create a “for loop” to create all of the visualizations at once!

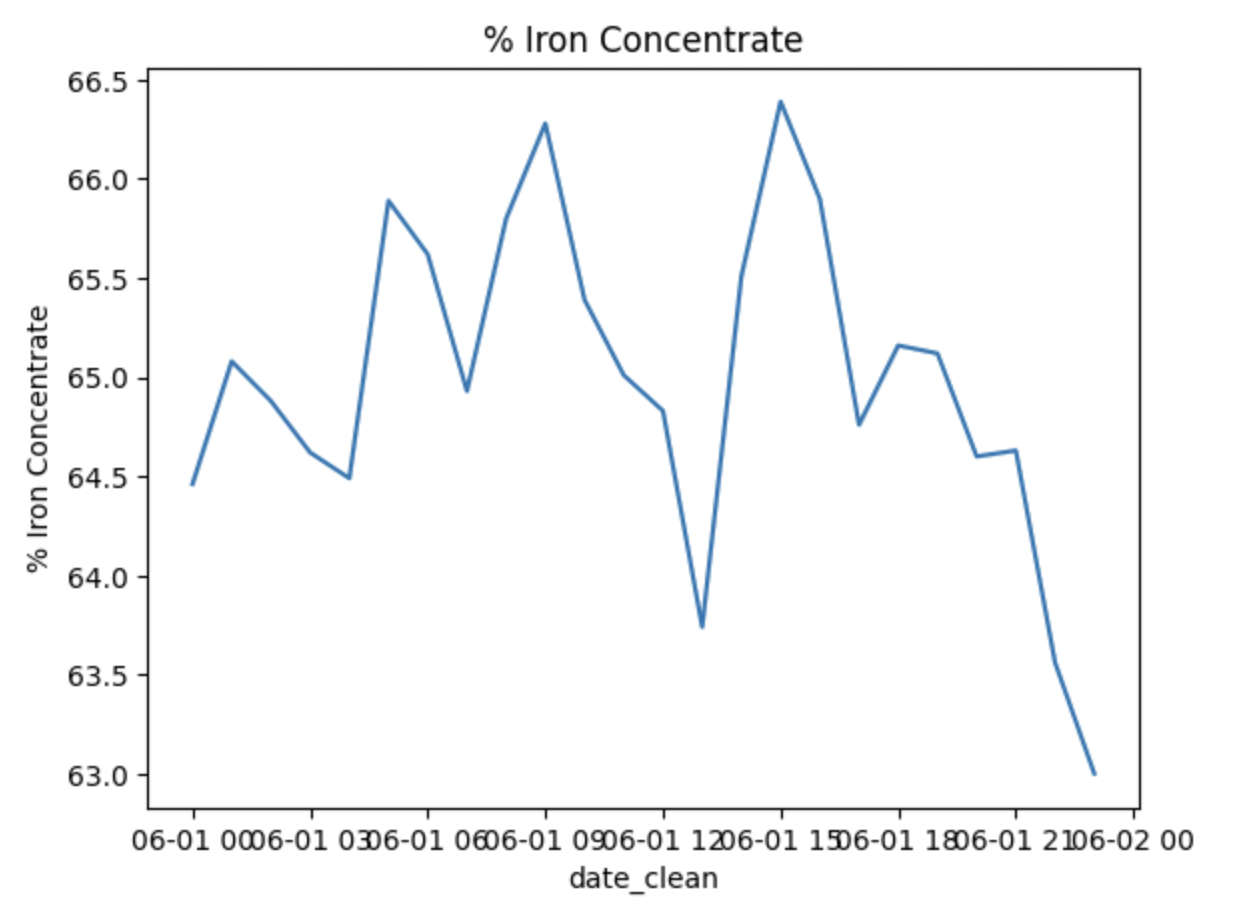

I first created another variable to represent the 4 series that I’m interested in (removing the date series). In the “for loop”, I’m starting by specifying the range by using the len function (meaning length) of the “imp_cols_nd” variable. I’m then asking Python to have “col_name” represent each of the values in “imp_cols_nd” and then specifying the parameters for each lineplot where x will equal the “date_clean” and y will equal the col_name which will change as the loop progresses and then lastly where to find that data. To finish out the code, I utilize matplotlib to help add detail to the lineplots like a title.

Here is the finished product:

Final Thoughts

At first glance, Python is intimidating. The code is unique and because of all the IDE’s available there are practically endless capabilities and uses. I definitely feel that I have a much better grasp on the tool and I’m excited to get even better acquainted with its power.